6/15/2023

A Closer Look at Jesse Brown at NASG

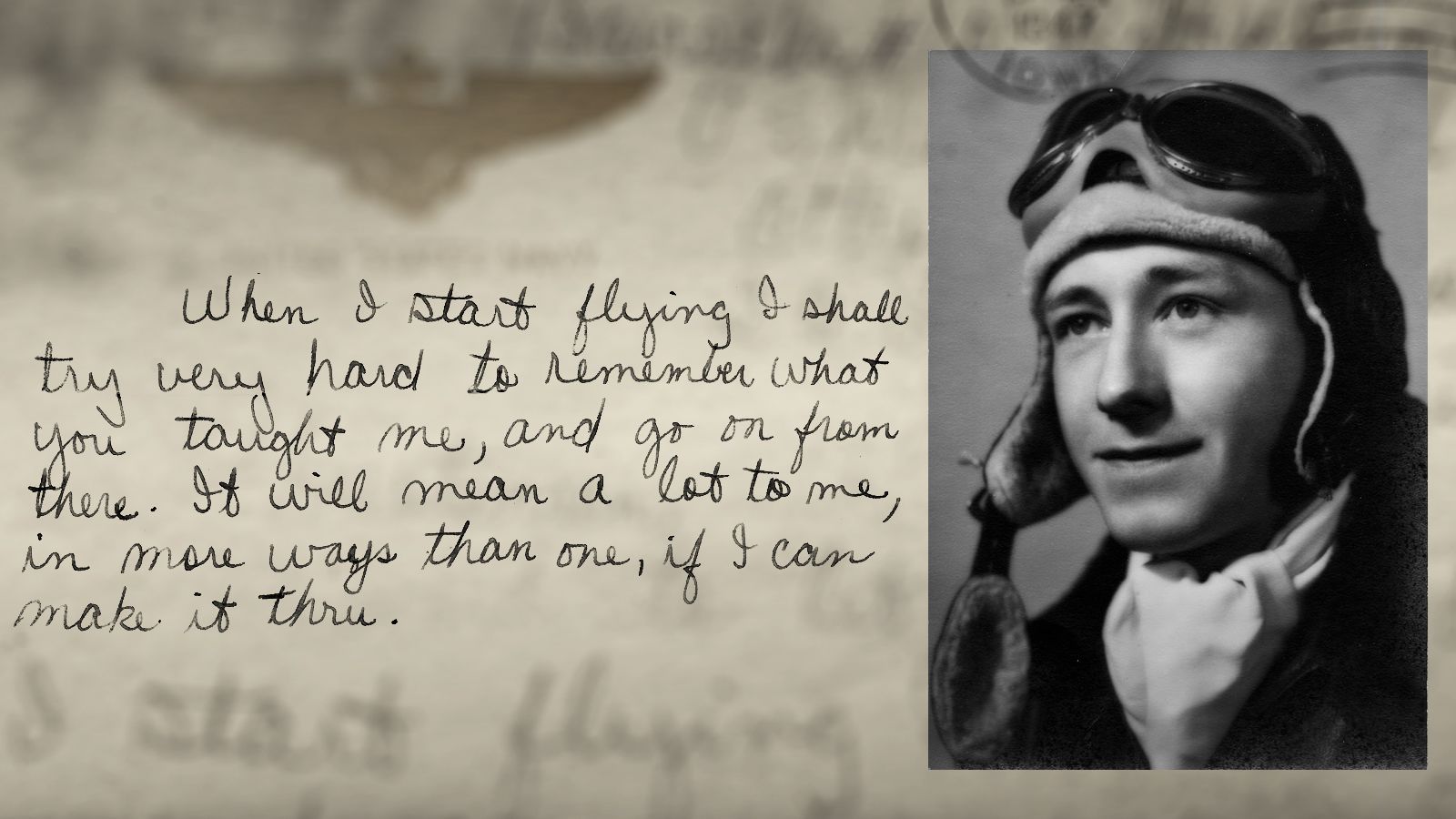

Glenview’s first reaction to Jesse Brown was a mixture of bewilderment, guarded interest, and silent hostility. Stepping off the train at Glenview station, Brown almost missed the bus to get to NASG because the bus driver, in disbelief that a Black man had official Apprentice Seaman orders, was convinced that Brown had gotten on the wrong bus. On his very first day at NASG, Brown’s appearance garnered the same reaction from the gate guard, the chief petty officer processing his orders, and his roommates. No one could believe it; there was a Black naval aviator cadet at Glenview.

After settling into his barracks, Brown took his first step into aviation with slight trepidation. Hundreds of cadets were milling around, checking the Morning Fight Boards to see which instructor they would be flying with. N2S-5 Yellow Perils were already taking to the sky, but Brown had yet to be paired with someone. Singled out, it appeared as though Brown wouldn’t even have a chance to prove himself in Pre-Flight—better known to the cadets as a routine weed-out day.

However, what Brown didn’t know was that LTJG Roland Christensen, better known as “Chris” to the other instructors, had seen his plight and thought he might need a friendly hand. A Nebraska native, Chris trained to be a combat fighter pilot and thus was quite unhappy to be spending his time teaching cadets. Nevertheless, despite having a reputation for being extremely strict about flying procedures, Chris was otherwise considered very easygoing.

Making his way over to the bored Flight Commander, Chris volunteered to teach Brown one-on-one. Cadets were required to complete eight or nine scheduled hops lasting a minimum of an hour and 15 minutes and then a solo flight to pass the program, and Brown had already gone through a merry-go-round of roommates who had dropped out due to extreme air sickness or simply after realizing they didn’t want to be a pilot after all.

Chris took Brown up on his first flight in one of the Yellow Perils and walked him through all the basics: takeoffs, landings, basic maneuvers, and emergency procedures. Despite Brown’s initial nervousness, Chris’ calm reassurance assuaged his fears and taught him to let the plane take control of his body and “go with it.” As he soared over Glenview, Brown experienced a whole new world far from earth, a private one he couldn’t wait to return to every day of his life.

Minutes after they landed, however, another instructor popped his head out of the ready room and jokingly called to Chris that he developed an “oil leak.” For Brown, the words were a slap to the face after the sheer joy and euphoria he felt only moments earlier. However, Chris ignored the jibe and instead told Brown to “ride with it” and not let the comments get to him.

Outside of flying, Brown maintained his athleticism and ended up joining NASG’s basketball team. However, when he flew to Pensacola to play against the station team there, he was told minutes before the game started that he couldn’t play because he was black and Florida, at the time, was still segregated. In fact, an official told his coach that he shouldn’t even have been allowed in the dressing room.

Nevertheless, Brown continued pushing himself to become an even better aviator despite the persisting attitude from his peers and instructors that he shouldn’t even have been there. On his ninth day, his last day of instruction, Chris wrote of Brown: “This student works very hard. Is interested and asks questions. He uses his head, thinks, makes corrections. Flies and holds attitudes good. Student is ready for solo.” Brown’s final test at Glenview had come.

On April 1, 1947, Brown headed out on a sunny Tuesday morning to the traffic pattern at Arlington Racetrack. Calming his nerves, Brown performed exceptionally well and skillfully guided his plane through takeoffs, landings, stalls, spins, and rectangular patterns. On the ground, Chris clapped him on the back and told him “I’m proud of you, Jesse, for a lot of reasons. I honestly think you’ll be a fine naval aviator.” Brown received similar feedback from a “check pilot,” who was employed by the Navy as a double guarantee that the cadet was indeed ready and did not pass simply because their instructors liked them and cut corners on the assessments. Breen, Brown’s “check pilot,” wrote in his report that he had “Good basic airwork. Soloed very well. Completed two safe solo landings.” Brown had done it; the dream he had since he was ten was well on its way to becoming reality.

Chris’ patience and gentleness encouraged Brown to pass Selective Flight Training with flying colors, and the two men continued to write to each other even after Brown left Glenview for Iowa for additional training. After learning of Brown’s death at the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, Chris was so impacted that he became a search and rescue pilot. Chris and Brown’s bond was reflective of the many that were formed at NASG, and the instruction cadets received here at Glenview would serve them well for the rest of their naval aviation careers.